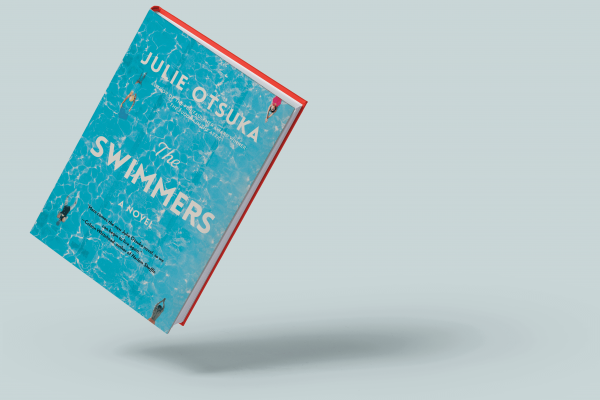

LET'S SAY YOU are a third of the way through Julie Otsuka’s latest book, The Swimmers, and someone asks you to describe the story. If you have encountered her second novel, The Buddha in the Attic, you might comment on the familiar reliability of the collective “We,” the prevalence of lists, the cataloguing of characters’ habits and choices.

But if you prefer to be concise (so you can return to your reading), you would say the novel is about a group of swimmers who belong to an underground pool in their town. Above ground, they struggle with “bad backs, fallen arches, shattered dreams, broken hearts, anxiety, melancholia, anhedonia,” among other afflictions. But down below, in the pool, they can rely on the consistency of lanes, their lap counts, and their rules. They can even tolerate occasional rule breakers and bad management. Everything makes sense until a mysterious crack appears at the bottom of the pool.

Soon, one crack develops into many. When experts cannot find the origin of the anomaly, it leads to one conclusion: The pool must close.

Read the Full Article