CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM in the United States is gaining momentum with each graphic video showing fatal police abuse. In the aftermath of the many deaths of unarmed black men and women and the city-wide protests that erupted in Ferguson, Baltimore, and Cleveland, it is not surprising that presidential hopefuls are making bold public statements about the need to change a system that is profoundly unjust, overly punitive, and excessively costly to run.

At the other end of the spectrum, away from TV cameras and political wrangling, activists such as Tara Libert and Kelli Taylor, co-founders of the Free Minds Book Club and Writing Workshop, are dealing with decades of draconian anti-crime policies that have resulted in mass incarceration rates marked by racial disparities that have had a devastating impact on families and communities.

The numbers speak for themselves. Although the United States makes up less than 5 percent of the world’s population, it has nearly 25 percent of its prison population. According to The Sentencing Project, a research and advocacy organization working to reform the U.S. criminal justice system, more than 2.2 million Americans are now locked up in prisons and jails across the country—a 500-percent increase over the past 30 years. Furthermore, those who are incarcerated come largely from the most disadvantaged segments of the population.

For Libert and Taylor, it all started in the mid-1990s, at the height of the so-called zero-tolerance policies on crime. As TV producers, both Libert and Taylor often reported on the criminal justice system, covering the death penalty, juvenile justice reform, and prison overcrowding. They saw firsthand the lack of educational and rehabilitative programs in prisons.

A long list of needs

In 1996, Taylor received a letter from Glen Charles McGinnis, a young inmate on death row in Texas. McGinnis wrote to ask reporters to cover the stories of young men of color sentenced to death throughout the country. McGinnis was 19 when he was found guilty of armed robbery and murder and sentenced as an adult.

Taylor produced a documentary about McGinnis, and in the process became his friend and mentor. They read the same books and discussed them through letters. Despite various attempts to commute his death sentence to life in prison, McGinnis was executed in 2000. “It was so heartbreaking and tragic,” recalls Libert in a recent interview with the Catalogue for Philanthropy. “We wanted to direct our pain and powerlessness into something positive, so we started conducting a book club and writing sessions at the D.C. Jail in 2002 in Glen’s memory,” Libert said.

McGinnis often is referred to as the “original Free Minds member” because of his love for reading and writing despite dropping out of school at age 11 and having little family support. McGinnis’ story prompted Taylor and Libert to focus their work on 16- and 17-year-olds charged as adults.

What started as a volunteer activity quickly became a vocation for both, explains Taylor. “We used to go to the jail every few weeks,” explains Taylor, “but the more we went, the more it became clear that this was bigger than what we originally thought. There was a long list of unfulfilled needs this population faced.”

Touching the “untouchables”

Activist and social commentator Angela Davis wrote in her book Are Prisons Obsolete? that when inmates are removed from society, society quickly forgets about them. It’s a way, Davis wrote, for ordinary people to distance themselves from the “undesirables ... relieving us of the responsibility of thinking about the real issues afflicting those communities from which prisoners are drawn in such disproportionate numbers.”

Prisoners are our version of the “untouchables,” says Taylor, while recalling how even her own educated friends sneered at her newfound vocation. Young inmates feel the social isolation even more deeply than older prisoners because they are separated from their families at a time when they need them most and have fewer coping skills to adapt to the prison environment.

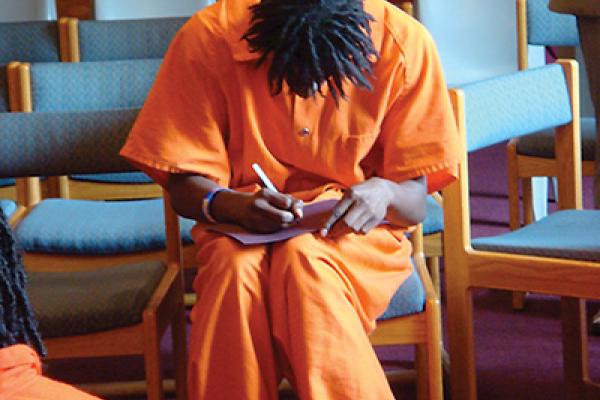

The goal of Free Minds is to introduce these young inmates to the transformative power of books and creative writing. “The idea for the book club started because I found books to be a powerful tool to connect with someone you have absolutely no history with,” says Taylor. “So we started with a book featuring a main character, Thai, who gets mixed up in the ‘street life.’ The character was someone very relatable for our young book club members. Kenji [Jasper], the author, is an African-American young man from D.C. The fact that all the locations in the book are actual places in D.C., and are accurately described as they are in real life, was a huge draw for youth to engage in reading for the first time.”

Fast forward 13 years and Free Minds now runs the book club in the D.C. Jail twice a week, is in regular contact with more than 350 inmates each year who have been transferred to federal prisons across the country, and offers a comprehensive re-entry support program to members that go home. In 2010, Free Minds launched On the Same Page, a violence-prevention program in which former inmates turned Poet Ambassadors speak to middle and high school children and to community groups about the root causes of youth incarceration. “Free Minds members have not just fallen through the cracks, but have been thrown into a chasm,” says Libert. “They are so far deep below and they are crying out for help and we cannot even hear them. Part of our mission is to share their voices, the untold stories. We use the tools of poetry and their own narratives to do this.”

Turning off the “macho man” mode

“When selecting books for youths in detention, we follow the five Es rule: engage, educate, empower, escape, and expand,” Libert explains. If the youth can relate to the characters and the story, she says, they are more likely to stay engaged and to keep on reading. The hardest part, though, might be getting the young inmates to overcome their lack of trust in people and join the book club. They do so for many reasons.

“Initially it was a way to get out of my cell in the juvenile block,” says Juan Peterson during a group discussion. “Slowly I gave in and started to write poems. I wrote about the experiences I had gone through and about my absent father. When we got feedback from people outside the jail, I was amazed how many people could relate to what I wrote.”

“I read books about young men similar to myself who went on journeys from negative to positive, such as Reymundo Sanchez in My Bloody Life: The Making of a Latin King, and Jimmy Santiago Baca in A Place to Stand,” says Will Avila, a Free Minds poet who spent five years in jail as a result of committing a crime while in a gang. “By talking about the books we read, I learned to share my ideas and to compromise. Everybody had their ‘macho man’ mode off during the time we spent in the book club.”

Club members choose the books they want to read from a long list of titles that expands as they get older. Free Minds will often arrange author visits to the D.C. Jail to meet with book club members. The objective is to give them hope because, in the words of former inmate turned motivational speaker and author Shaka Senghor, “Your worst deeds do not have to define you.”

Caged-in talent

Reading is the first step in expanding the mind, but writing is how the inner journey truly begins. Poetry, the group’s co-founders say, has a way of breaking down stereotypes and misconceptions and getting to the raw humanity that connects all human beings. “Books and poetry are only tools, though,” says Libert. “Their true power is in the connections they foster.”

Avila says that reading and writing changed his perspective on life. “When I was angry or frustrated about life, instead of doing something outrageous I would start to write,” he explains. “When I read other people’s poetry, I realized that we all share the same feelings, that we all make mistakes.” Avila is now co-owner of Clean Decisions, a cleaning and maintenance company committed to training and hiring former inmates.

This interactive healing process is at the core of Write Nights—a community activity in which ex-convicts read poems written by their incarcerated peers to ordinary citizens. The audience then can give written feedback on the poems and Free Minds will deliver it to the D.C. Jail. Creating connections with the outside world, says Libert, demonstrates that someone—a stranger—cares enough to take the time to consider something they produced and write to them. And others agree that it’s a powerful idea: At the Aspen Ideas Festival this summer, Free Minds received a $25,000 first-place prize to help cities around the country implement the Write Nights program in their own communities.

“As I read the poems, I could not help but be amazed at all the talent that has been caged in,” writes Kenneth, a Free Minds poet and a co-editor of the first poetry anthology published by Free Minds. “I was proud to know these young men were like me, struggling against the demon of the caged, fighting every day to become something different—something better—something no less magnificent.”

Dealing with root causes

Free Minds members speak out about the root causes of mass incarceration at congressional briefings and community events. They know firsthand the reasons why so many of their peers are either in jail or dead. A cemetery is only a few blocks away from the D.C. Jail and is visible from inside the prison.

In a report titled “The Poor Get Prison: The Alarming Spread of the Criminalization of Poverty,” authors Karen Dolan and Jodi L. Carr argue there is increasing evidence that poverty and incarceration rates are inextricably linked by a system that profits from criminal charges disproportionately affecting people who are already struggling to get by.

A case in point is Ferguson, Mo. Using data from an investigation conducted by the United States Department of Justice into the Ferguson Police Department, Dolan and Carr explain that the city was “relying on fees, fines, and court costs for 20 percent of its budget ... with a 95 percent white police force supporting itself by forcibly preying on a nearly 70 percent black population.”

While there is increasing consent on prison reform thanks to initiatives such as #cut50, a bipartisan movement led by Van Jones and Newt Gingrich that seeks to reduce the incarcerated population by 50 percent over the next 10 years, what must also be tackled is the systemic racial discrimination that lands many young men of color in jail and a perverse logic that puts fund raising ahead of public safety.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!