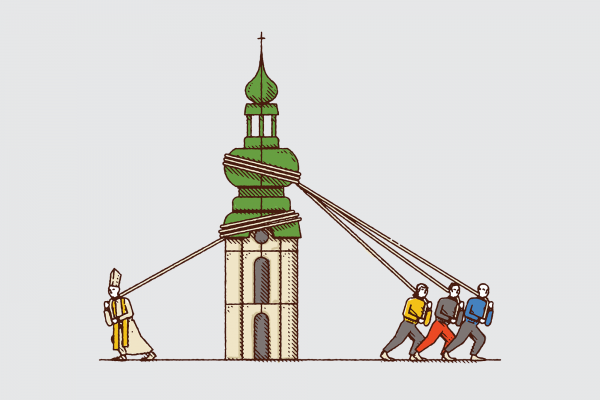

IN OCTOBER LAST year, protesters stood silently in the streets of Kraków and Szczecin in Poland. This gathering was not criticizing the ruling political party. Instead, their banners bore the slogan “We Want the Church Back,” echoing “We Are the Church” movements directed at the Catholic hierarchy by laity around the world.

These Roman Catholics call to account sermons offered by conservative Polish clergy. The clerical leadership is “dividing people and spreading hostility toward others instead of teaching about our merciful God,” the group explained in a petition. Many Catholics in Poland feel homeless because they experience hostility, condemnation, and exclusion from the pulpit. They want to publicly demonstrate that the Catholic Church is larger than priests and bishops; that everyone, regardless of their sexual orientation or minority status, should be able to find a place in the church that calls itself catholic (which means “universal”). Finally, they demand that the priests and bishops not reject Pope Francis’ message and that Catholic social teaching, the church doctrines on human dignity and common good in society, be returned to the mainstream of Catholic life.

A month later in Gdańsk, 150 members of the archdiocese protested the bishops’ negligent handing of sexual abuse cases. They were responding to a study by the conference of bishops released in March that noted nearly 400 cases of Polish priests accused of abuse of minors between 1990 and 2018 and to the release of a documentary, Don’t Tell Anyone, in which priests are confronted by their victims. The hierarchy refused to investigate reported incidents and failed to openly support the victims. Lay Catholics also specifically criticized Gdańsk’s Archbishop Sławoj Leszek Głódź for his lavish lifestyle and confrontational communication style.

Read the Full Article