TWO OF MY favorite television shows are Finding Your Roots with Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Who Do You Think You Are? Both shows walk celebrities through the process of discovering their ancestors’ stories. I could watch them for hours (and sometimes have).

I love them, but I am also frustrated by them. Because the history of American families is American history, those families’ stories inevitably intersect with major U.S. events: the removal and genocide of Native Americans, slavery, the Salem witch trials, the suffrage movement, prohibition, the great migration, Jim Crow, the list goes on. Usually, these shows give about one minute for celebrities to process their ancestors’ roles in these monumental moments, then move on. Celebrities whose ancestors participated in American westward expansion are often celebrated as “pioneers” whose courage and grit helped forge America. Rarely are they guided to understand that their ancestors participated in the removal and genocide of Indigenous nations who stewarded the same land for tens of thousands of years before Europeans “pioneered” it.

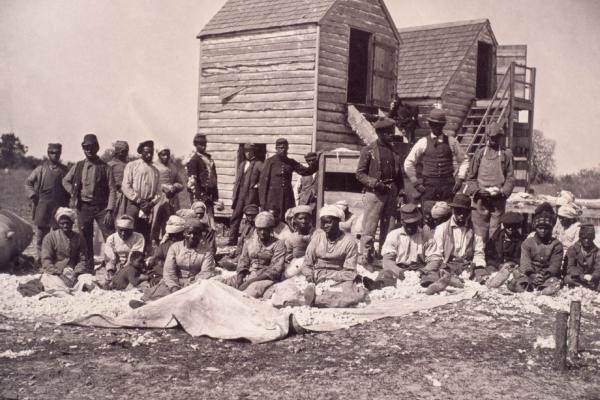

Recently, I dug into the story of my third great-grandmother, Lea Ballard, who is the last adult enslaved person in our family. Her daughter, Martha, died while giving birth to my great-grandmother, Elizabeth.

Read the Full Article