BEFORE THE PULSE NIGHTCLUB SHOOTING in 2016, the worst act of violence against an LGBTQ gathering in American history unfolded in 1973 at a bar in Louisiana frequented by members of a gay church. The Metropolitan Community Church of New Orleans lost nearly one-third of their congregation in a Sunday night arson attack at the UpStairs Lounge, a working-class drinking hole where the faithful often gathered after church services.

Most Americans have never heard of the UpStairs Lounge—or for that matter, Metropolitan Community Churches (MCC). Yet half a century ago, MCC was the largest gay organization in the United States.

You read that right. By the mid-1970s, the largest gay organization in the United States was a Christian denomination.

Founded in 1968, one year prior to the Stonewall Riots, MCC would find its greatest success in the U.S. South, with congregations sprouting from Florida to Texas to small towns all across the Bible Belt.

Today, there are approximately 100 MCC churches in the United States, with over 40 in the South. But a generation ago, there were more than double that amount. From South Carolina to Alabama, local congregations have dwindled. Many have closed their doors; others are on life support. Dallas’ MCC shuttered in 2018. Charlotte’s MCC turned out the lights in 2022. According to recent research by William Stell, faculty fellow at New York University and author of Born Again Queer, at least 40 Southern MCCs in the past 30 years have disappeared.

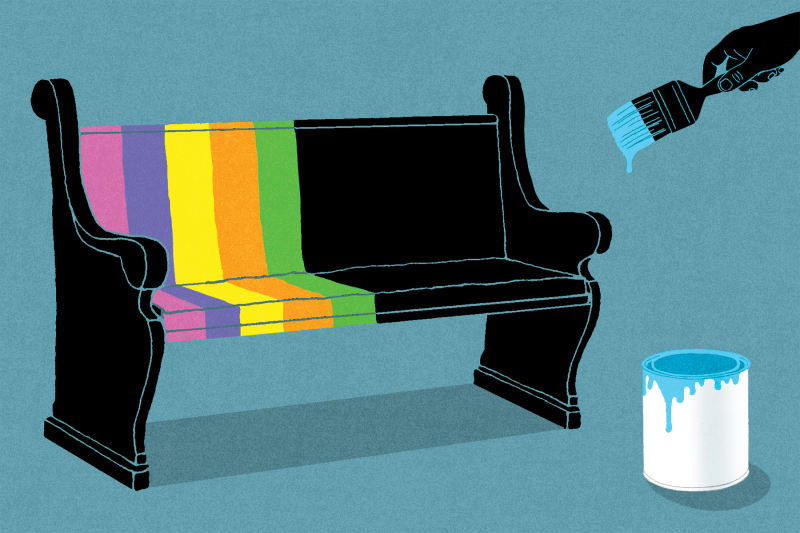

UCLA’s Williams Institute reports that the South is home to more LGBTQ Americans than any other part of the country. But as church membership among all Americans sinks to historic lows, and LGBTQ people find increasing acceptance in once-hostile, now-welcoming mainstream congregations, what role does an unmistakably gay church, born out of the fires of Gay Liberation in the 1960s and ’70s, play in the contemporary South?

Comfort in the familiar

MCC’S FOUNDER, Troy Perry, “is certainly a Southerner,” historian Robert W. Fieseler, who chronicled the church’s early years in his book Tinderbox, told Sojourners. “He’s never lost the accent. He’s never lost the swagger and style of who he is as an ex-Pentecostal pastor from Florida.”

When Perry’s marriage fell apart in the 1960s and he moved from northern Florida to southern California to start over as an out gay man, he carried a distinct brand of Southern Christianity with him.

The early rituals of MCC worship emerged from Perry’s “backwater Pentecostal” style, said Stell, who is writing a biography of Perry. “It’s definitely not the case that every MCC church is a Pentecostal church.” Yet it is also true that “all sorts of things about the MCC at large reflect the Pentecostal upbringing of its founder.” These include the use of call and response patterns, claps and shouts of hallelujah, and stories of healings. “In some cases, stories of miracles. In some cases, stories of speaking [in tongues].”

By the mid-1970s, the largest gay organization in the United States was a Christian denomination.

Perhaps it is surprising to think of Southern gay men and lesbians finding comfort in the very rituals that emerged from the churches where they endured the fire and brimstone of anti-gay sermons as children. But that’s what makes the MCC so popular in the South, said Catherine Houchins, a retired MCC pastor in Roanoke, Va. “Ideally, when you’d walk into an MCC, if you were of a Christian background you would find something that felt Baptist, something that felt Methodist.”

Houchins’ own experience is illustrative. Raised Southern Baptist, she first stepped foot inside an MCC church in Norfolk, Va., as a 31-year-old newly out lesbian in the 1980s. “I walked in, and ... they were singing ‘Because He Lives.’” Houchins knew the hymn from her Baptist upbringing. She was expecting something different, something foreign, yet found MCC worship to be surprisingly connective with her Southern heritage. “It just felt totally comfortable.”

Many of MCC’s early pastors were raised in, and sometimes ordained in, Southern Baptist or Pentecostal denominations. That was also true of Terri Steed Pierce, senior pastor at Joy MCC in Orlando, Fla., who led MCC’s response to the Pulse nightclub shooting in 2016. Pierce was raised Southern Baptist, and by the time she was in high school in North Carolina in the 1980s, she knew she wanted to be a preacher. However, in her church, “Women could be music people or children’s people. They could do announcements, but never a prayer.” Things got more complicated when she enrolled in seminary. During her first year, she fell in love with another woman—one of her classmates. “You know, coming out as gay in a Baptist seminary in 1989. Yeah, not recommended.”

When she stepped foot inside an MCC for the first time, in Raleigh in the 1990s, she didn’t know what to expect. “Gay church? How’s that work? It just seems oxymoronic.”

A collection basket, inexplicably filled with oranges, was passed down the pew. A church member grew the oranges in his own backyard. “When he passed that damn basket around, when it got to me, I swear to you, I saw myself in the basket,” Pierce said. “You know, I’m gay, I’m female, I’m called. And if oranges can grow in North Carolina, [then] Terri, a lesbian, called-of-God female, can do all this. I can be all of who I am.”

MCC’s growth in the South in the 1980s and 1990s was nothing short of extraordinary. According to Stell, a 1978 MCC directory detailed 101 total congregations, missions, and interest groups in the U.S., with 29% in the South; by 1995 there were an astonishing 221 MCCs nationwide, with nearly 40% in the South. MCC was growing—and becoming more Southern.

MCC’s southernization reflected national trends in American Christianity at the time. This was the era of emerging large-scale megachurches led by charismatic televangelists. Southern evangelicalism was ascendant on the national stage, both religiously and politically. Stell explains that MCC, with its own firebrands, sought to build on the larger church growth movement within evangelicalism at the time. “They literally said, ‘We are going to double in 10 years.’” When the ex-Pentecostal minister Don Eastman took over leadership at Dallas’ MCC, known as the Cathedral of Hope, in the late 1970s, he was able to build that church into the largest MCC congregation in the world—a megachurch for Southern gay people.

Houchins remembers national conventions in the 1980s and ’90s. Then, “You might be in a ballroom with 1,500 [or even] 2,000 LGBT-affirming allies.” There would be people speaking different languages, pastors hobnobbing with lay delegates. When the ballroom was packed for worship and for convocations, Houchins said, “it was just amazing.”

But the good times wouldn’t last.

dec feature rosenthal 2.png

A crisis of identity

BY THE TURN of the 21st century, the national gay landscape was shifting underfoot like tectonic plates. Many mainstream LGBTQ organizations in the 1990s began to reposition themselves, both strategically and rhetorically, toward a new politics of acceptance and assimilation. In response, queer activists and scholars warned that “equality” might mean losing those distinctive spaces that queer people had long maintained for safety and community, such as gay neighborhoods, bars, and even gay churches.

By the early 2000s, several mainstream Christian denominations began opening their doors to gay Christians, posing an existential challenge to MCC. In more than half a dozen interviews with pastors and scholars, nearly everyone said a version of the same thing: The greatest challenge the denomination has faced in the past 20 years is captured in the following euphemisms: open, affirming, welcoming.

A majority of the South’s MCCs have disappeared since 1995.

The future became clear in 2003 when the Cathedral of Hope—MCC’s largest church—voted to disaffiliate from the denomination. With more than a thousand members, the Cathedral reportedly took almost 10% of MCC’s national membership with it. Three years later, the congregation joined the United Church of Christ (UCC), a mainstream liberal denomination.

Individuals also voted with their feet, frequently returning to the churches they were raised in as those denominations became more welcoming. “People go back to what they know,” Pierce said.

Houchins is more critical. It is, she explains, “a blessing and a challenge that other churches are open and accepting.” Yet there are levels of acceptance. “Some churches will say, ‘Everyone’s welcome. You’re welcome to come. You’re welcome to give.’ But you may not be welcome to sing in the choir. You may not be welcome to work with children. You may not be welcome to hold offices or be clergy.”

In Florida, where MCC has retained some regional strength, Brendan Y. Boone, a leader in MCC’s People of African Descent ministry, said that the denomination cannot survive by attempting to “out-gay” other liberal denominations. “I reject that,” he said. “When people say, ‘Oh, is that the gay church?’” He replies, “No, we’re not the gay church. We’re a Christian church with a special outreach to the LGBTQIA+ community.” He wants MCC to be open and affirming in the other direction, too, to “straight allies and heterosexual couples”—people who, he said, have helped change the face of the church in positive ways. Boone believes the denomination needs rebranding—from “the gay church” to “the human rights church.”

Nancy Wilson, who led the denomination as MCC’s global moderator in the 2000s and 2010s, adds that MCC’s identity crisis is less about sexual orientation than it is about class. “MCC is a working-class movement,” she explains. She contends that pastors and congregants seeking to switch over to the UCC or other liberal denominations have class aspirations, noting that “MCC has never been known for paying pastors well, and we don’t have institutional financial strength. We’re upstart. [We’re] bootstrap.”

Like many denominations, MCC’s once-rapid growth has come back to bite many of its congregations, as aging infrastructure has become an albatross around their necks. “The Methodist church we bought,” Houchins said, of her former congregation’s once-stately edifice, “was beautiful, but everything was old.” With maintenance costs piling up, the Roanoke congregation sold their building in 2022. Meanwhile, Charlotte’s MCC kept refinancing its building through church bonds. Soon, a $4,000 per month mortgage had ballooned to $12,000 per month. They sold their building in 2014 and went completely under eight years later. “A lot of people are tied to their community of faith’s building,” Houchins said. When a padlock gets affixed to the front doors of their beloved sanctuary, people start looking for a new church—even if their congregation continues meeting elsewhere.

MCC’s decline has been stark. According to Stell’s research, a majority of the South’s MCCs have disappeared since 1995. Georgia once had as many as six MCCs; today there is only one. Alabama, Kentucky, South Carolina, and Tennessee each had four congregations; now each has one. Arkansas once had four, as did Mississippi; today, there are no MCCs in either state. In total, as many as 45 Southern MCCs have either ceased to exist or never really got off the ground. Only Florida and Texas remain bastions of denominational strength in the South, as over a dozen congregations worship in each state.

“And if oranges can grow in North Carolina, [then] Terri, a lesbian, called-of-God female, can do all this. I can be all of who I am.”

Pierce said there is just one way for small churches like hers to survive, and that is through change. Since the Pulse shooting, Joy MCC has been more active in the local community. “[We] march, not just for gay people, but we march for Black Lives Matter. We did the No Kings march. We did the Women’s March.” Their visibility has attracted a new generation of congregants. Once overwhelmingly “white and older,” Pierce said, “people of color and straight people have come, too, and children.” The congregation recently started a children’s ministry. They have placed non-gay congregants in leadership roles.

Boone concurs that MCC needs to do more to attract both straight people and people of color by inviting in “the people who are standing outside the door looking in and don’t see anybody that looks like them.” MCC needs to ask itself tough questions, he said: “Where are we going? Who are we? What’s our mission? What’s our focus? What sets us apart from everybody else? Until we can answer, we’re going to struggle.”

dec feature rosenthal 3.png

A living church

IT’S 95 DEGREES on a Sunday afternoon in Roanoke. Inside an inconspicuous, ranch-style Church of Divine Science building on a dead-end street, six miles from the city center, 40 chairs are arranged facing a stage. As the service begins, less than half of them are occupied.

Rhonda Thorne, who was installed in 2022 as the congregation’s pastor, leads the church in prayer. Wearing a striped polo shirt and clerical collar, she preaches in a distinctly Southern style, raising the rhythm and pitch of her voice, then suddenly bringing it down to a whisper punctuated by dramatic silences.

Halfway through the service, a deacon passes around a collection basket. The church needs to raise $682.69 a week to keep the lights on.

Communion at MCC is open to all. Individuals, couples, and families approach the front. The pastor and deacons hold these supplicants in prayer, eyes closed, heads bowed, hands grasping arms.

After the service, the church gathers for homemade strawberry cake. It’s a tradition on the last Sunday of the month to celebrate birthdays, and today is MCC founder Troy Perry’s 85th. This is still a living church.

As I make my way outside, I chat with a 30-year-old nonbinary person who just began attending MCC nine months ago. They grew up evangelical and had been stomaching their way through an “affirming” evangelical church downtown, until a church leader made a statement condemning trans people as “groomers.” Today, they sing in the music ministry at MCC. They are visibly radiating with joy.

On the edge of this small city, in the heart of the Bible Belt, a Metropolitan Community Church is still guiding queer Southerners home.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!