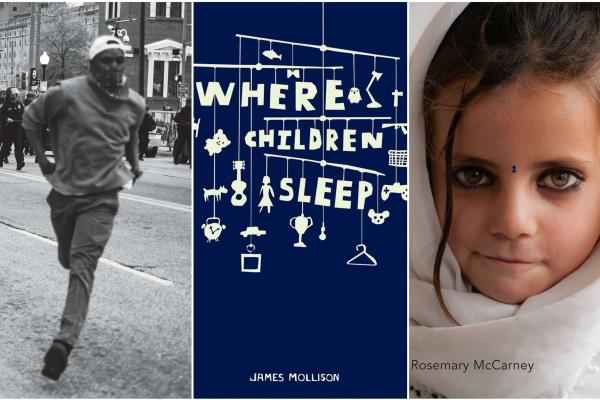

BOOKS ARE WINDOWS into other worlds and glimpses of experiences not our own. One of the most powerful ways books have worked in my life is to illuminate the truth that the world is a very unequal place. It started at a young age for me, my childish mind consumed with stories such as that of Helen Keller (and her teacher, Anne Sullivan, who for several years lived in a “poorhouse”) and missionary biographies of people such as Amy Carmichael and Gladys Aylward, who worked with children who had been trafficked or orphaned in other countries.

Even as a child I puzzled over why some children suffered so greatly and others didn’t. It wasn’t fair.

As much as I loved stories with fairy-tale endings, such as The Secret Garden or The Little Princess, I returned constantly to narrative nonfiction that exposed me to a wider, morally complex world. And this drive never left me.

Today, there are many books that address the topic of inequality in fresh, insightful, and provoking ways.

Read the Full Article