The straw mat at their door read "GO AWAY." Few, it seems, took this seriously. Drawn together years earlier by common interest in theology and social ethics and a strong personal bond, William Stringfellow and Anthony Towne left New York in the fall of 1967 in body, if not entirely in spirit. They established a place for rest, reflection, and writing on 14 acres of land overlooking the cliffs and Old Harbor of New Shoreham, Block Island, Rhode Island.

Anthony Towne was a satirist best known for his farcical obituary of God written lightheartedly at the expense of the "Death of God" theologians. His poetry was published in many journals and periodicals. He contributed thoughtful, often humorous, and always insightful narratives to volumes that he co-authored with Stringfellow.

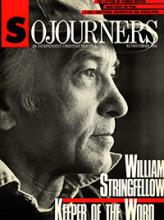

There could scarcely have been a sharper physical contrast between these two men: Towne, a towering hulk of a man, full beard giving him a somber, almost threatening look belied by his personality; and Stringfellow, since his radical surgery in the late 1960s, a frail echo of his former self, seemingly only half the size of Towne. Life for Stringfellow and Towne was essentially a theological vocation. According to Stringfellow, "Every person, if they reflect upon the event of their own life in this world, is a theologian." One day when first on the island, peering off into the Atlantic from the fog-shrouded cliffs near their house, a friend remarked, "It seems like the end of the world." Thereafter they called their home "Eschaton." They later described Eschaton as "our own monastery."

At Eschaton hospitality was gratuitously extended to pilgrims of various sorts who happened through in a seemingly unending string. There was abundant physical nourishment, some gleaned from Towne's garden plot.

Read the Full Article