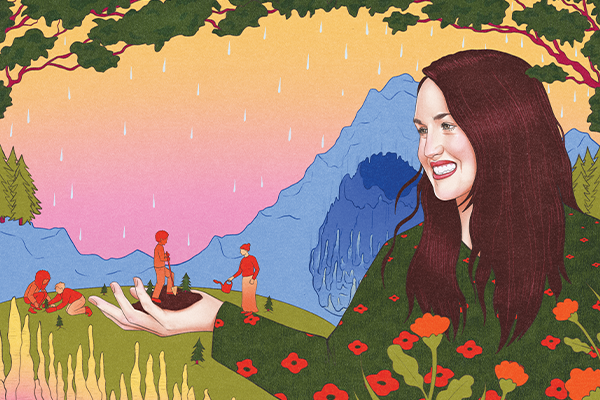

JESSICA MOERMAN SPENT years in Malaysian caves and Kenyan lake beds unearthing clues about ancient climate. But when she speaks about the climate change we’re experiencing today she takes a different approach: She begins with scripture.

Moerman, 38, is both a trained climate scientist and an evangelical Christian who espouses a faith of action, not just talk. “I am a climate scientist because of my faith,” she told me.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login