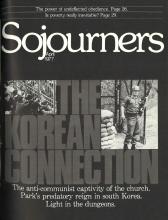

Rev. Park Hyung Gyu has been pastor of the 300-member Jeil (First) Presbyterian Church in Seoul since October, 1971, and chairman of the Seoul Metropolitan Community Organization (SMCO) since its founding in September, 1971. The 53 year old Park (no relation to the South Korean President Park Chung Hee) served two churches before becoming general secretary of the Korean Student Christian Movement in the ‘60s.

After a merger of Korean student organizations in 1969, he became editor of a monthly magazine, Christian Thought. He served one year as program director of the Christian Broadcasting System in Seoul until forced to resign after the national election of 1971. He chose to become a Congregational pastor again and, with Jeil Church as a base, initiated a number of inner city programs. The SMCO, one of the more creative and successful programs, has helped to organize squatters in every major slum in and around Seoul.

Park is committed to proclaiming the gospel of liberation to the poor and oppressed. He is also committed to basic human and democratic rights. As a result, the present dictatorship has considered him a double threat and has arrested him four times. In 1973 and again in 1974 he was charged with “plotting to overthrow the government by force.”

The first charge resulted from Park’s alleged connection with leaflets distributed at an Easter sunrise service. The leaflets bore such messages as “God have mercy on our foolish king.” The 1974 charge was based on Park’s support for students who planned (but never carried off) a peaceful demonstration for the restoration of democracy.

In 1975 he was charged with “embezzling church funds”--SMCO funds which he had authorized for legitimate SMCO projects. Last June he was detained on suspicion of “communist activity.” Park has spent nearly half of the last four years in prison.

Read the Full Article